To this day, indigenous people live in the United States. Whether it be the Apache Nation, Cherokee Nation, or the Pueblo Nation. But not only in the south of the United States but also far up in the north there are indigenous people groups. Located in the northwest corner of Washington state on the northernmost coast a sovereign indigenous nation, the Lummi People live. The Lummi nation has its own government and laws and consists of approximately 6,600 People. For centuries, their culture has depended on the Sea, Salmons, and everything the nature has given to them.

Context

Due to the ongoing opioid crises in the United States and the epidemic of addiction and overdose death the Lummi nation unfortunately is also affected by this crisis. As the matter of facts, the crisis is even more serious for the Lummi people as there is a 3.5 times higher age-adjusted mortality rate from opioid overdoses among the Lummi People than in Washington State as a whole.

As former Executive Medical Director at the Lummi Tribal Health Center, Dr. Justin Iwasaki was responsible for the daily primary care of people dealing with health problems due to the opioid crisis. Knowing that his view was only one way to see the opioid problems he was seeing the opioid crisis unfold day by day.

To help the Lummi people to stem or even solve the problems they are facing through the crisis, Dr. Iwasaki knew that it was crucial to understand the root of the systemic problem the people are facing. Because of Justin Iwasakis previous Job redesigning public health systems, Dr. Iwasaki was familiar with the concept of Design Thinking.

Participants and Activities

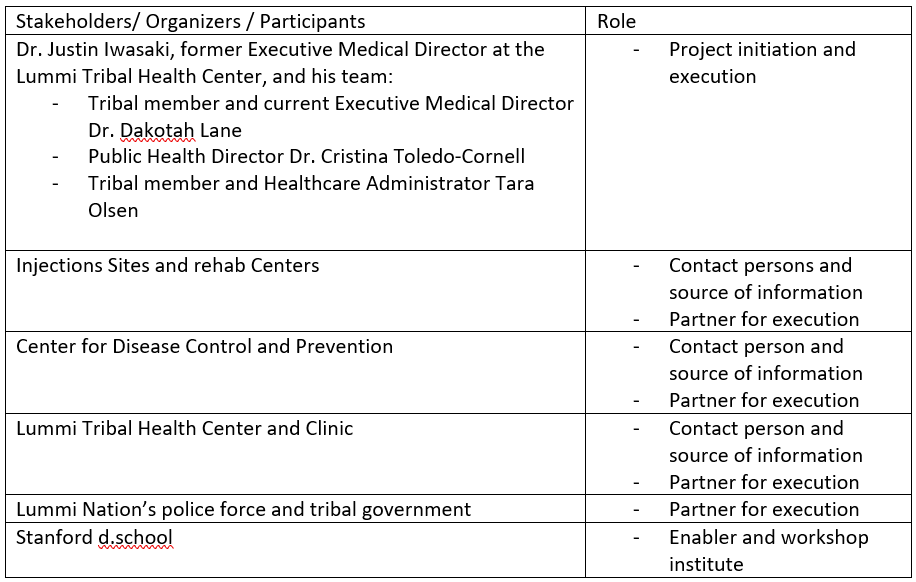

The kickoff for developing a prevention strategy came in 2018, when Justin received funding from the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Following the announcement of this grant, Dr Iwasaki formed a team of four. The team included tribal member and current Executive Medical Director Dr. Dakotah Lane, Public Health Director Dr. Cristina Toledo-Cornell, and tribal member and Healthcare Administrator Tara Olsen. To bring all these team members on the same page and to acquire relevant design thinking inspiration, tools and mindsets, Justin initialized the attendance of the Standford d.school´s Fall Designing for Social Systems (DSS) workshop. After the participation, the team had one philosophy particularly memorized: Let the people you serve guide the design.

As Design thinking is an approach for human-centered, creative problem solving it does not only help developing or improving (new) products. This approach can also be used for something more important: Developing and improving socially important structures and Systems (e.g. here: Part of the Health Care System). In this way we can use this approach, which originally stems from the economy, for a better future.

Regarding the five phases of Design Thinking (Empathize, Define, Ideate, Prototype, Test) the team began their work by visiting and observing injection sites and rehabilitation centers in the US and in Canada. They found out, that while there are different models of prevention/ overdose prevention in Canada like supervised injection sites among other things, in the United States there is only one Model with addiction issues namely an abstinence only approach. The problem with this approach is, that this total abstinence is not realistic for many people. The Lummi team was therefore interested in exploring this alternative from Canada because it is more human-centered since it aims to understand what the peoples needs really are and how the can help them using drugs safely and less.

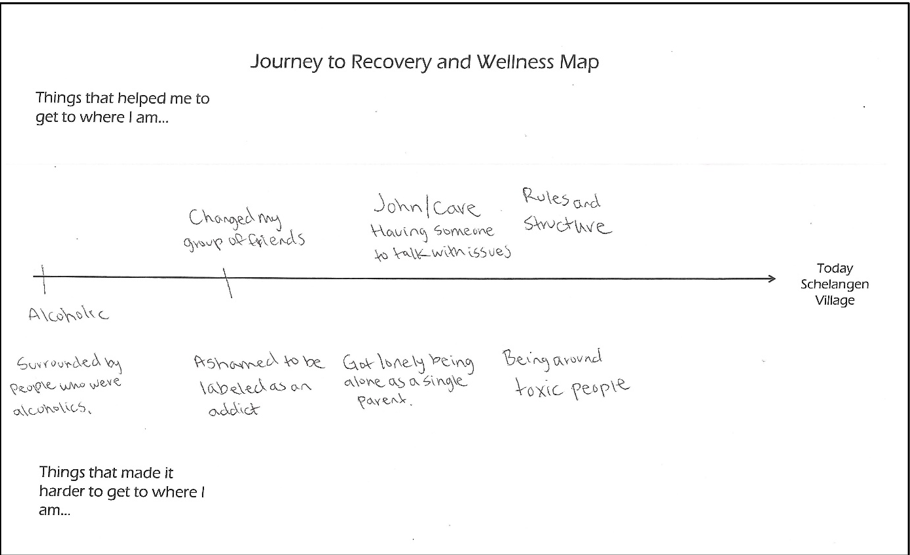

After the site visits the team wanted to understand the individual fates of members of the Lummi Nation. They talked to 35 members in an 1-on-1 interview situation. All these people were call on to visualize their “Journey to Recovery and Wellness” in a map. In this Map the participants wrote down there experience with opioid use. The team learned about this kind of approach/ tool of Journey mapping in their workshop at the Stanford d.School. By talking to the people Dr. Justin Iwasaki and his team learned about personal problems but also about structural problems that the tribal members who are addicted to opioid are facing.

Obviously, there are barriers that makes it difficult for the people to get the treatment and help they need. For example, to that time current treatments were only available in-person and only during specific times. Also because of the abstinence only model they need to show up five to six times per week to receive medications for opioid use disorder. These insights form the interviews and Journey Maps shows the team how the affected people actually feel: Many patients found this treatment model punishing and undermining their trust, making them uncomfortable to seek help. Therefore, they defined their goal: Services and treatments needs to be more human-centered and accessible. So, the problem was not only about medication, but the methods in which care is provided to the people.

After they empathized with the people and defined the problem the next step was about ideating ways that could solve the problem. As you will see the phases ideate and prototype kind of merges seamlessly in the following actions.

First the team focused on services redesign. They decided to try three new approaches:

- A low barrier Medication Assisted Treatment Program

- Community-based harm reduction program

- Peer counselor outreach service

The first key point should help to make the treatments more accessible. Instead of direct patient observation while they are taking the medication the new program prescribes the medication from the Lummi Clinic, available at the same day in-person or via telemedicine by one of the doctors. Through this approach the people can pick up the medication and take it whenever it fits into their schedule. Because of this form of tailoring the treatment it is also a way to make the service more human-centered.

The second bullet point is also about making the services more accessible. By recruiting participants of the existing harm reduction program as (team-)members of the new program. As a member of the program, one would be provided sufficient safer injection supplies to redistribute these supplies to their existing networks on the other side. Therefore, patients would no longer be required to go to the clinic to receive injections supplies.

With the peer counselor outreach service, the team setup an approach, where people with a history of substance use disorder helping existing patients. By opening informal avenues people addicted to opioid can discuss with people who can empathize with them because of their history. In case of an overdose the counselors receive a text message so that they can quickly offer their support. Also they check in on the patients in their own homes to make in more comfortable an accessible for them.

While focusing on the service redesign the team also thought about the system redesign. The interviews and the evaluation of the people’s journey maps point out, that a lot of the interviewees were in prison. Often the reason was their substance use disorder. But not only that they were in prison because of there addiction to opioids they were getting out and the consume and the rate of overdoses increases. They found out that ~40% of fatal overdoses among Lummi tribal members occurred within 60 days of being released from jail. It is a kind of a vicious circle. Justin and his team worked for criminal justice reforms to decriminalize minor crimes like drug paraphernalia. By keeping the people out of jail, they wouldn’t enter the described vicious circle. In winter 2020 the law to decriminalize drug paraphernalia was passed.

Results

Since the project is still quite young there are not really any results published. Because of the work of Dr. Justin Iwasaki and his team there is now more than one model/ the abstinence-only-model to tackling the opioid addiction. They evolved a service system which is clearly more huma-centric and accessible. Also, they successfully reformed the criminal justice system. These are results they have achieved so for. The overall goal to minimize the rate of overdoses and opioid addicted people in general can neither be declared as achieved nor as not achieved due to the lack of data.

Lessons learned

What this case study of a design thinking application teaches us is that Design Thinking is not only about solving problems for companies so that they can economically benefit from the approach. It is not only about developing or improving a process, an experience, or a product in an economically sense. Design Thinking can be used for a better future, health, and environment. Problems occur in our daily lives but not all problems are business cases. Sometimes or even often we suffer from structural problems and difficulties regarding e.g., the health system like in this case. By empathizing with the patients or affected people we understand their need for a better well being and for better future. Another example of using Design Thinking in a social or environmental context is a project from Fridays for Future in Oldenburg. The team worked on the problem of climate communication and how to communicate the challenges of the rising climate crisis and how to communicate what each of us must change without constantly calling to restrictions and waivers.

In my opinion using the approach of Design Thinking in social and ecological situations and challenges should be supported due to its importance for the mental and physical health of us and our environment.